Where You're From or Where You're At

Mapping Rappers in London

Shorter version originally presented at the European Hip Hop Conference at University of Bristol in 2019

Introduction

To quote Sun Ra (1973), ‘space is the place’, and there is no style of music more grounded in place than hip hop. Hip hop ‘takes the city and its multiple spaces as the foundation of its cultural production’, grounding the music geographically through a combination of place marks, vocabulary and aural composition (Forman, 2000: 67). At the heart of a lot of hip hop is some reference to place. This can appear at several different scales, from the country (USA), to the city (New York), to the neighbourhood (The Bronx), to the street (Sedgewick Avenue) and even occasionally to the individual building (15-20). Place forms a key identifier for many rappers both musically and visually and examples can be found everywhere. As a result, there is a large amount of spatial data within hip hop, which is often taken for granted aurally as just part of the music and the blueprint of the style. There is the potential, however, for this data to be extracted and analysed spatially, which could help provide some interesting insights not just into hip hop and rappers but also into the locality from which they are from.

With a focus on London, this research looks at where rappers emerge within the city. This is often the most common form of spatial data to be heard in UK hip hop and its even more locally defined offshoots such as grime, drill and road rap. Place and postcodes form an identifiable marker in a large proportion of this music as ‘MCs tend to make a big deal about their place of birth’ (Bradley, 2009: 126). In particular, the aim of this research is to examine the feasibility of extracting this spatial data from hip hop music and how it could be used. In order to test this, an analysis of the spatial distribution of rappers in the city will be attempted; with the intention to both assess how this has changed over time as well as to see if it is possible to identify potential local hip hop scenes using clustering mapping techniques.

Mapping and Music

We come across maps every day, whether we're aware of it or not. While in the past many of these maps would have been physical, increasingly we now consume maps digitally; generally either as an indicative static map, such as in a news article, or through web maps via Geographic Information Systems (GIS), such as Google Maps (Maguire, 1991; Google, 2019). Unlike static maps, GIS allows users to interact with spatial data to find what is relevant to them, like the location of a friend’s house or the nearest cinema. GIS can also enable users to analyse this data, statistically and spatially, to identify potential patterns and insights that can help inform others about the data in question (Unwin, 1996).

Very rarely, however, do we see data related to music mapped. This is very much reflected in academia where little research has been done on how the two media can be brought together. Much of those studies of music using mapping as the focus, have tended to focus on infrastructure and physical aspects such as radio stations disseminating polka music (Sinton & Huber, 2007) or a proposed approach by Matthew Allen to map the evolution of the guitar (Lund, 2007). Additionally, Taylor et al (2014) have used GIS to chart changes in the music scenes of Sydney and Melbourne through the dissemination of live music venues throughout those cities. Another approach has been to use the artist origin or the style of the music as the geographic markers to generate maps. These tend to use the internet and web scraping as the methods of determining the origins of performers. The internet has multiple places where this information can be found, but so far very few attempts have been made to harness this data and visualise the results. One example is the use of an origin classifier, developed through web extraction, to map the artists featured on radio playlists showing the geographic spread of music being played and potentially having the ability to link artists by location (Govaerts & Duval, 2009). In a similar vein, an attempt has also been made to create geographic maps of a person’s music collection through harvesting origin data extracted from Wikipedia and Last FM and visualised in the GeoMuzik platform (Celma & Nunes, 2008).

‘Examples of research that make maps of music are still something of a novelty’ and this is still very much the case when it comes to mapping musicians or performers (Taylor et al, 2014: 1). While some have attempted to map musicians’ birthplaces in the context of other research, very little has been done in this area (Carney, 2003). Place and origin can be big markers towards understanding identity representation, but these are aspects that are often ignored due to the complexity and transitory nature of many musicians and styles of music that transcend traditional borders (Krims, 2007). The few that do marry mapping with information about performers tend to focus more on mapping the personal memory of music scenes to musicians, creating their own hand-drawn maps of the city that could then potentially be transposed into a GIS. Examples of this include Cohen’s (2012) and Lashua’s (2011) work on music in Liverpool focusing on rock and hip hop performers.

Space, Place and Hip Hop

The relationship between hip hop and place is an often-discussed topic within hip hop studies, with everything from flow, sound, video, style and image analysed and defined within the context of a local or global hip hop scene. Popular music ‘alters our understanding of the local’ but it also ‘augments our appreciation of place’ and the identities that can be developed out of it (Lipsitz, 1994: 3). The expansion of the internet and smart technologies, however, has allowed people to access ever-growing levels of information without leaving their homes. As a result, it could be argued that ‘the increasingly global nature of communication…. has made the non-local community an increasingly common affair’ (Schloss, 2004: 4), suggesting that the concept of a locality focused music style is somewhat obsolete. Nevertheless, geography and geographical theory play a key role within hip hop where place is an important identifiable symbol (Jeffries, 2011). It could perhaps be argued then, that hip hop is one of the few modern genres to still be grounded in place in this increasingly globalised world.

Doreen Massey states that ‘places can be conceptualised in terms of the social interactions which they tie together’ (1994: 155), and this can be seen in hip hop through the interactions between fans and artists as well as the continual visual, aural and lyrical references that point back to a particular place or locality. This focus on place can potentially be seen as ‘necessarily reactionary’ as it attempts to ground hip hop in a location while technology and public rhetoric pushes a focus on the global (ibid: 147). By placing emphasis on the local through telling the stories of the ‘streets’, the music can give a voice to marginalised people that pushes those often silenced and demonised by the state and media into the purview of the public (Jeffries, 2011). At the same time, however, it is impossible to analyse hip hop spatially without taking into account the external global influences that will have had an impact in exposing people to the genre and helping localised styles to develop.

Hip hop is extremely geographical in its nature. Geography plays an important role in identity representation as well as helping to establish audience connection. Hip hop music is commonly grounded around a place and this is often articulated through reference points such as the name or a neighbourhood of that locality or identifiable landmarks (Back, 1996; Hess, 2009). While some dismiss geographic markers, such as administrative boundaries, as arbitrary and meaningless, within hip hop ‘postcodes and home territories matter’ and these territories are often defined by the ‘invisible borders’ of postcode and borough extents (Cohen, 2012: 142). This can be seen in the common use of postcodes, zip codes or even telephone area codes for representation on record (Forman, 2002). This focus by rappers on aspects of a specific location develops from a sense of ‘belonging’ that enforces a sense of place around their neighbourhood (Cresswell, 1996). There appears to be a need with performers to ‘speak the language of (their) own streets’ that allows rappers to align themselves within their communities and to address the question of ‘where am I?’ in relation to their surroundings (Du Noyer, 2010: 265; Bondi, 1993). This geographical representation can, in turn, shape those identities and potentially change the location itself, through stigmatisation or, conversely, popularisation resulting from the music (Hall, 1997). This can also be contested and challenged in hip hop through changing the question of ‘where am I?’ into an assertion that ‘I am here’. Examples of that defiance can appear both in the braggadocio raps so often associated with hip hop as well as the geographical markers being emphasised.

UK hip hop is no different in using references to place. Until recently, hip hop in the UK was often compared as the poor cousin to hip hop in America with little record label interest and limited sales (Hesmondhalgh & Melville, 2001). Due to this and the fragmented nature of local hip hop scenes at the time, a number of early rappers sought to cement a relationship with their audience through the use of geographic and cultural landmarks as well as accent that set them apart from American rappers (Codrington, 2005). These references, like London or Hackney, helped convey images of that place that develop a connection with their audience, when previously that same audience would have been consuming music talking about somewhere thousands of miles away. While this initially started as a means to distinguish UK hip hop from its American equivalent, the approach has been taken further to distinguish hip hop across the UK from that coming out of London. London has often been the dominant focal point in UK hip hop, with much of the infrastructure and a large majority of artists being based there. This has led to a number of rappers moving to the city in search of success in hip hop, as well as some rappers putting on imitative London accents to sound somewhat more authentic by suggesting they come from the capital city. Something similar to what happened in the early years of UK hip hop where rappers adopted fake American accents (Emery, 2009). Much of this comes out of the idea of wanting to imitate the 'dominant definition' of what they see hip hop as in order to appear authentic to both peers and audiences (Bourdieu, 1993:42; Speers, 2017). More recently, however, there has been a push by performers outside of London to differentiate themselves from the capital by using their own regional accents and local landmarks more on record.

While UK hip hop has tended to focus geographically on the city or town as an identifier, some of its offshoots, in grime and drill, have focused on more granular markers, particularly the postcode or the name of the council estate they come from. Grime emerged out of East London in the early 2000's, while drill appeared in the 2010's in South London, but for both, place has been a core part of the music. Location, such as Bow, and postcode, like E3, regularly appear in lyrics as rappers 'rep their ends', with those letters and numbers being so important to identity for some that having the wrong one can put you in serious danger (Reynolds, 2009: 78). Some of this is potentially connected to the pirate radio stations that helped disseminate grime and whose signals often barely stretched beyond a postcode boundary (Bradley, 2013). As a result, the rappers were often reaching out to those in their neighbourhood or stepping into others' territory where their home location was a badge of honour to be represented (Hancox, 2018). Similarly, drill groups often use postcodes and the names of council estates, sometimes even naming themselves after them, to emphasise where they are from and as a means of representation as well as a form of territoriality presented as a warning to outsiders.

Much has been written about the connection between place and hip hop. However, while there have been content and aural analyses assessing the role of place as a significant identifier, there has been little to no attempt so far in academia to represent this relationship spatially or to consider the possibilities of doing so. The rest of this paper will look at whether this is possible and, if so, what analysis could be done on this information to further enhance our understanding of it.

Collecting the Data

In order to perform any spatial analysis on hip hop, however, data first needs to be collected so there is something to do that analysis on. This in itself is no easy task as there is no rapper spatial data repository the data can be downloaded from. Any information to be analysed has to be collated from scratch. For the purposes of this research, this collection of information took on a two-pronged approach as first a list of rappers was identified and then efforts were made to append a geographic location to each one.

Compiling a list of performers began informally through discussions with peers and other fans of UK hip hop, with the intention of having a range across the history of hip hop in the UK from 1980-2019. While undertaking these discussions, the decision was taken to include, where appropriate, rappers both as individuals and as part of the group they also performed in. The reason for this was that in most cases, they were known as much for their solo work as they were for the releases made while in the group and solo careers often lasted longer than those of groups. At the conclusion of these debates, an assessment was done on the list and further online research occurred if there were any gaps or limitations identified. Much of this involved searching the internet using tags that are often used to categorise music, such as “UK hip hop” (Lambiotte & Ausloos, 2006). These tags can ‘serve as references in a discourse about music or they can be useful to discover similar artists’ through the groupings that this categorisation can create (Knees et al, 2008: 1). Such groupings are very useful in identifying fan sites, interviews or even databases compiled by amateurs that can help with research of this kind in filling in the gaps. At the end of this first stage of research, a list of 530 performers from London was compiled.

The next challenge was to identify where exactly in London these performers were from and when they were active based on their first and last releases. This involved using a Python script to perform automated web searches through a search engine using the keywords “Artist Name (i.e. Akala)”, “London”, “Rap” and “Hip hop” (Python, 2019). The decision was taken to use these keywords due to the similarity of some rapper names to general words that have other connotations, for example Blade or Chip. By using these keywords only pages related to hip hop and rap would appear meaning they would more likely be relevant to the rapper being searched (Knees et al, 2008). The first page of results were then scraped for mentions of place names stored in a dictionary using the additional library Beautiful Soup (Richardson, 2019). This place data was obtained from a spreadsheet file downloaded from the Ordnance Survey from which locations within London such as Hackney or Peckham were extracted (Ordnance Survey, 2019). The text then went through a number of filters to remove anomalies such as the names of venues or streets and the frequency of these place names was then counted with the place with the most occurrences being tagged to the artist as their point of origin. Another script scraped Bandcamp and Discogs pages for each rapper to identify the dates of releases, such as singles, EPs or albums. This script again used keyword searches in a search engine, this time using “Artist Name”, “London”, “Rap”, “Discogs” and “Bandcamp”. The resulting pages were then scanned for any release dates between 1980 and 2019, with the earliest and latest dates taken to indicate the years the performer was active.

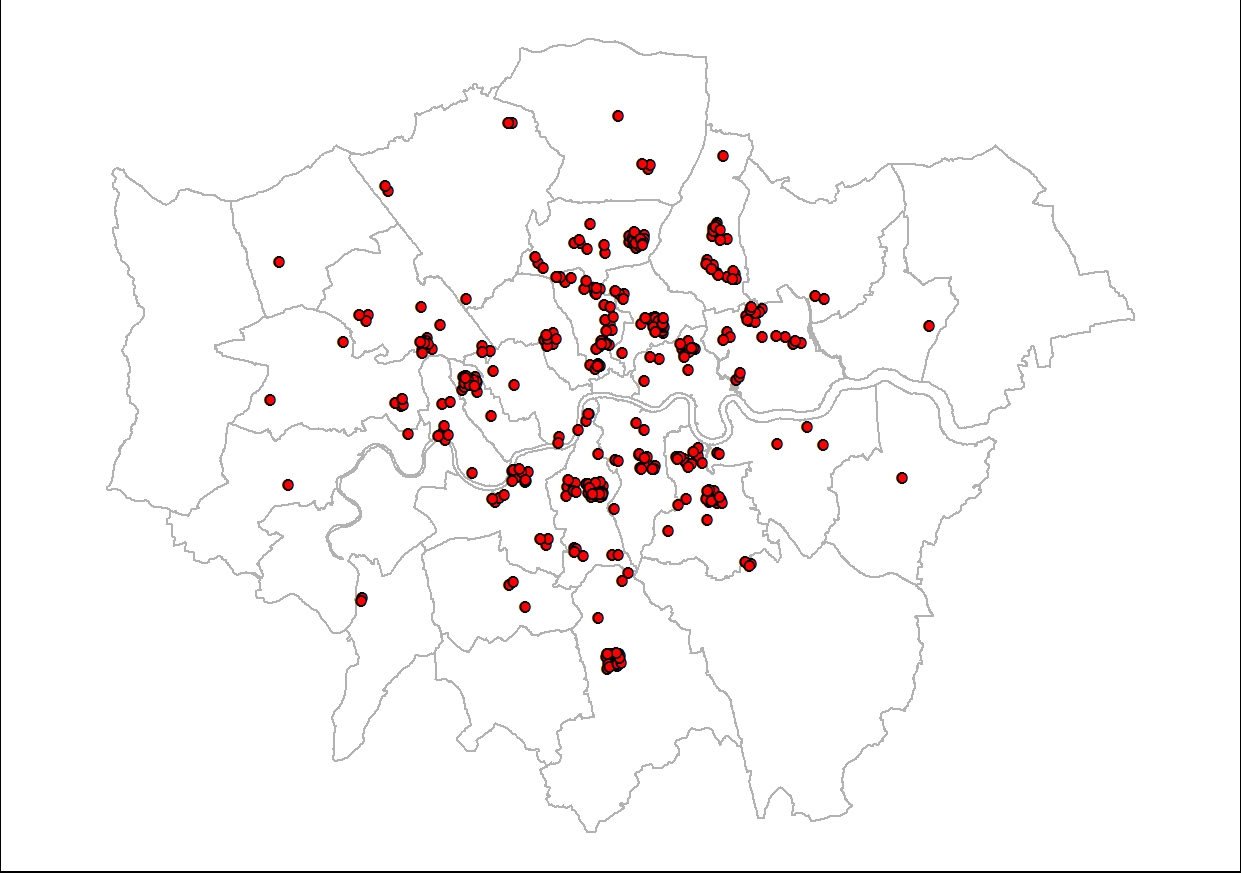

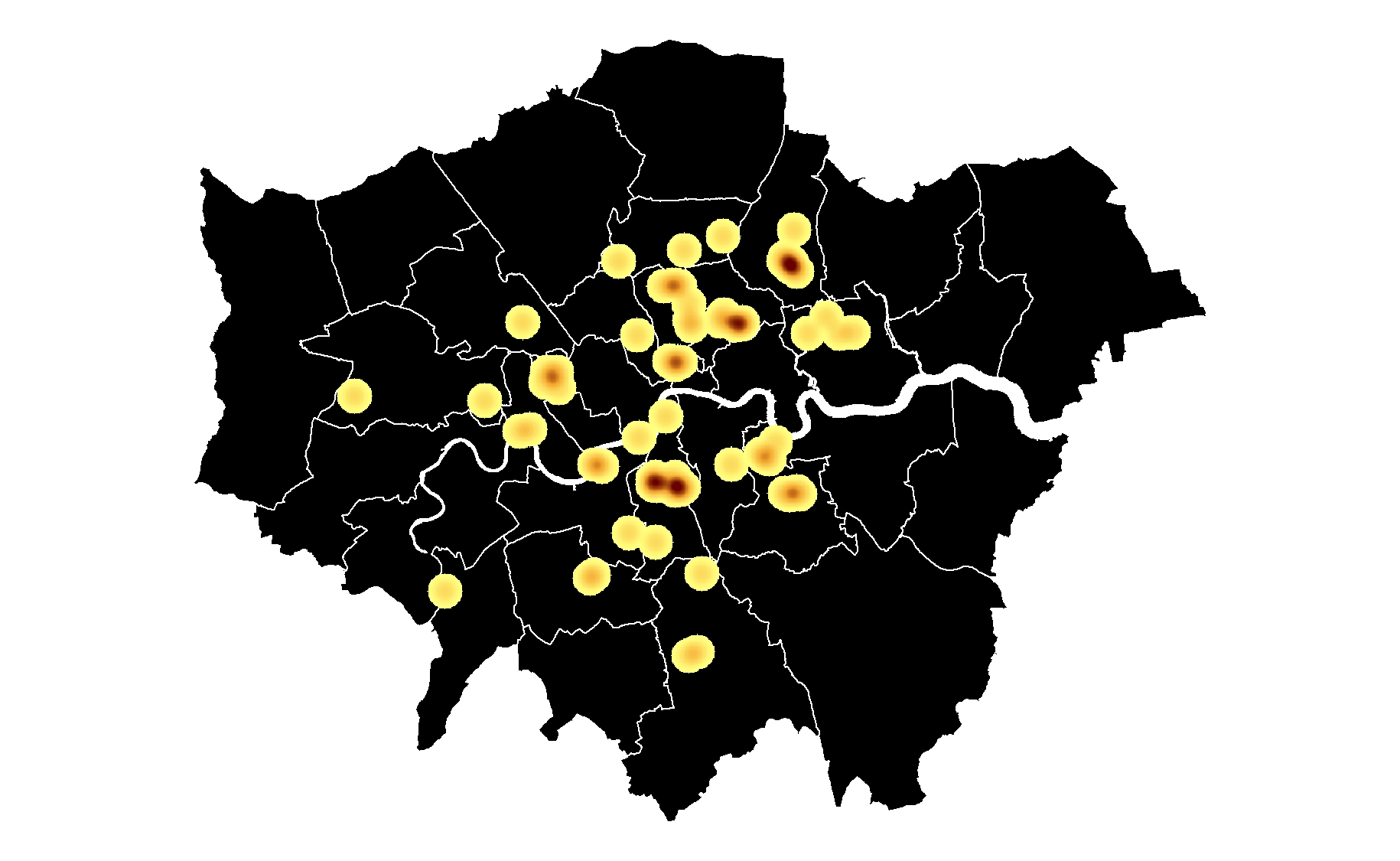

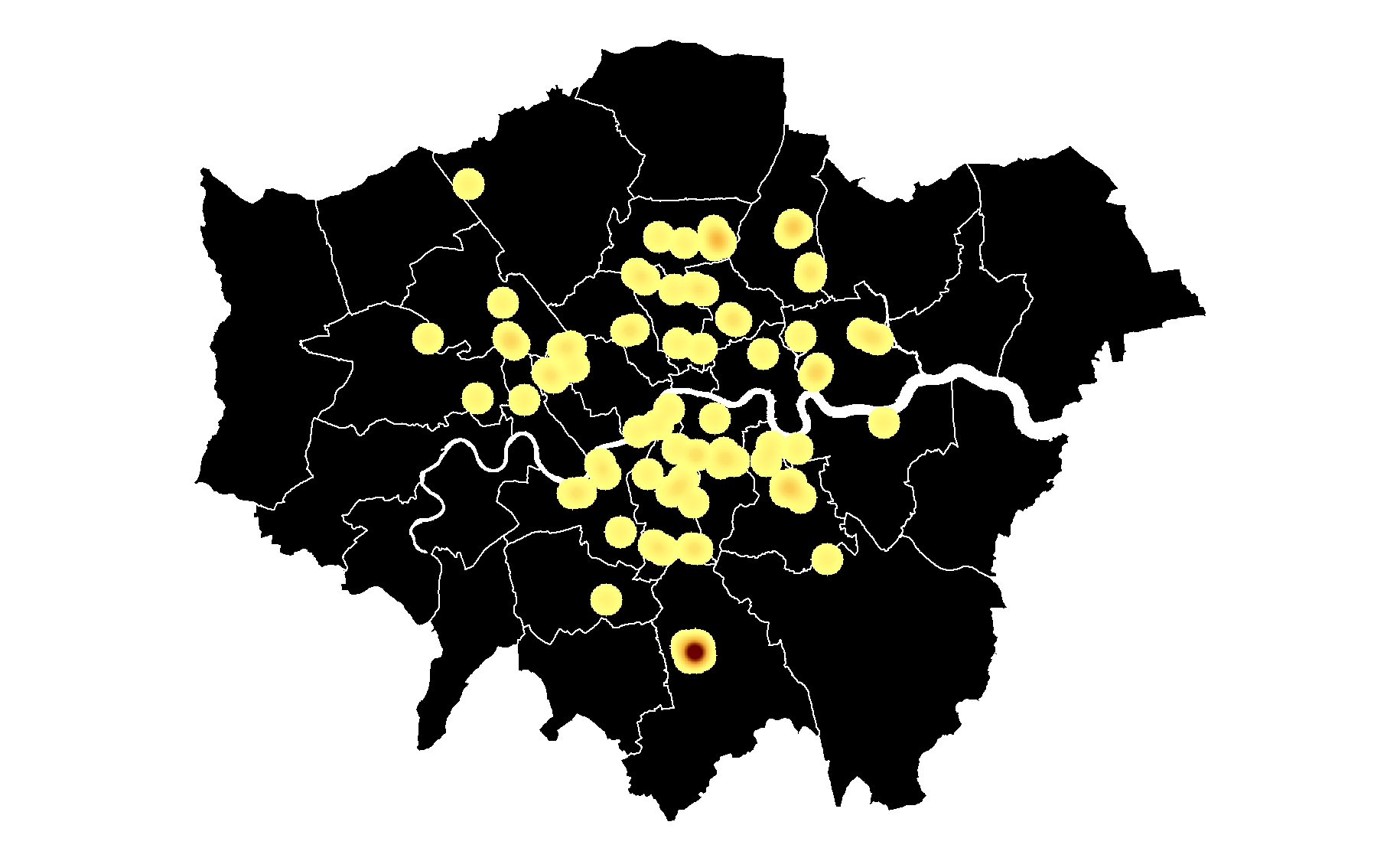

Using these automated approaches, the resulting data had an accuracy of approximately 60% in providing a correct or acceptable location and dates for the relevant performer. Of the 40% where the results were insufficient, for many of these the scripts were unable to find an acceptable location to place the performer or provided more than one answer because two locations received the same count. For these, further investigation was required and more detailed research revealed that for a number of these no geographic location beyond London could be identified. As a result, these performers had to be removed from the data as for the purposes of analysis, having data at different scales would lead to inaccurate results. Nevertheless, this still left 410 performers from which spatial information could be identified and mapped and potential analysis undertaken to find out more (Figure 1).

Statistical Analysis

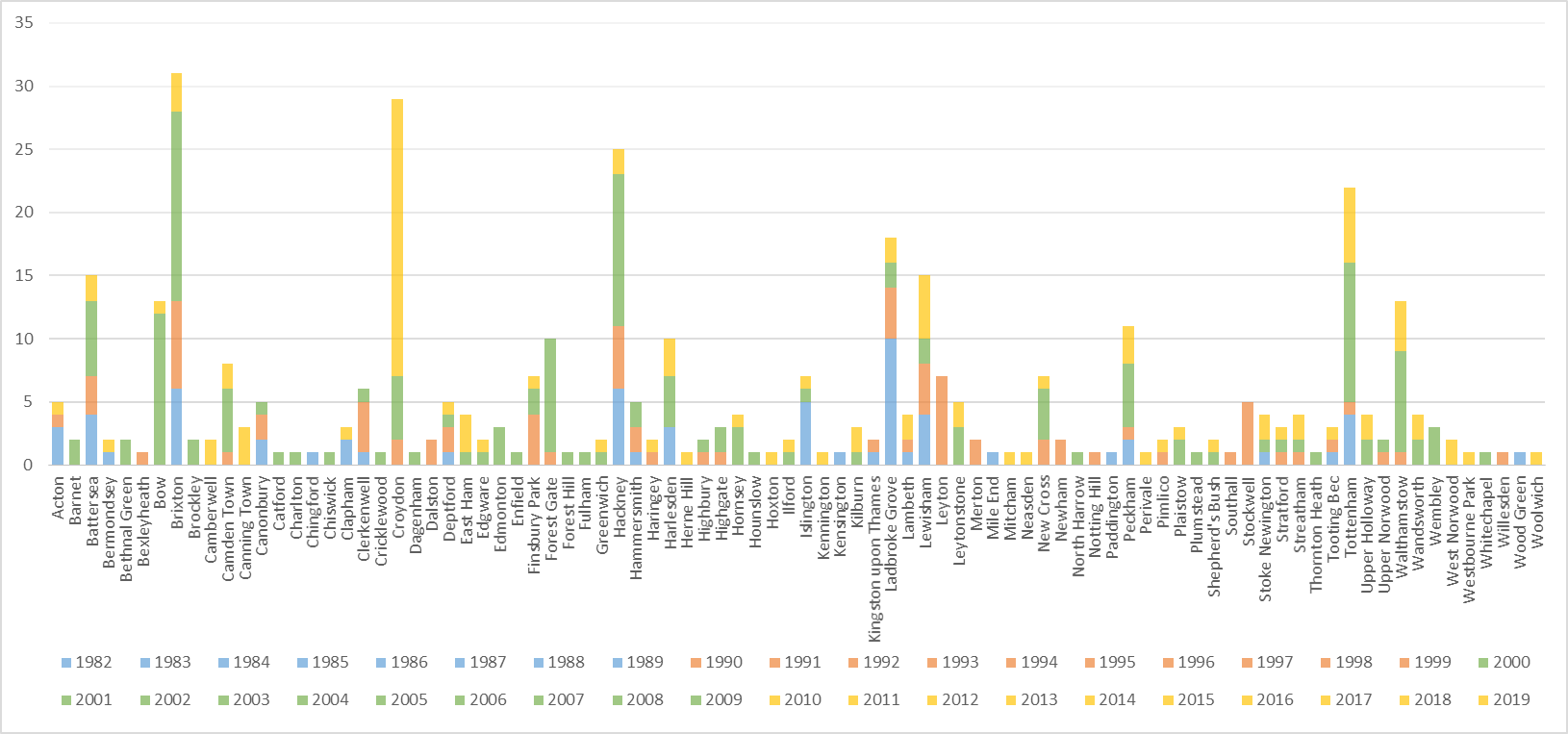

Taking these 410 points and conducting some statistical analysis on the information harvested, begins to reveal more about hip hop in London. By focusing on the locations (Figure 2), this starts to show that the distribution of performers across the city is weighted more heavily towards some places than others. While this can be seen with just points on the map, with the density of points greater in some areas than others, it can be a lot harder to get an understanding of the numbers involved without some additional investigation.

Immediately it becomes clear that Brixton, Croydon, Hackney, Tottenham and Ladbroke Grove are the most represented, with each having more than 15 performers attached to that location. Historically, these are some of the more prominent locations mentioned when talking about hip hop in London, with each place being significant at different periods. Taking a closer look at the colours, this becomes clearer as places have more of one colour than another. The colours represent different decades with blue for the 1980s, red for the 1990s, green for the 2000s and gold for the years since 2010. When looking at the data in this way, it can be seen that some places have been pretty consistently represented throughout these decades. In particular, Brixton and Hackney have strong numbers in each decade giving the impression that they have been important places for the development of rappers in London since the very beginning. In contrast, looking at somewhere like Ladbroke Grove blue is very much the dominant colour suggesting it was a key area in the 1980s for hip hop in the city. This situation is even more noticeable when looking at Croydon and Bow where the vast majority of the bar is taken up by one colour, the 2000s for Bow and 2010 onwards for Croydon. This suggests that these two locations were particularly significant in producing hip hop performers in those decades, potentially indicating the influence of some form of a local hip hop scene given the high number of performers appearing in such a short space of time.

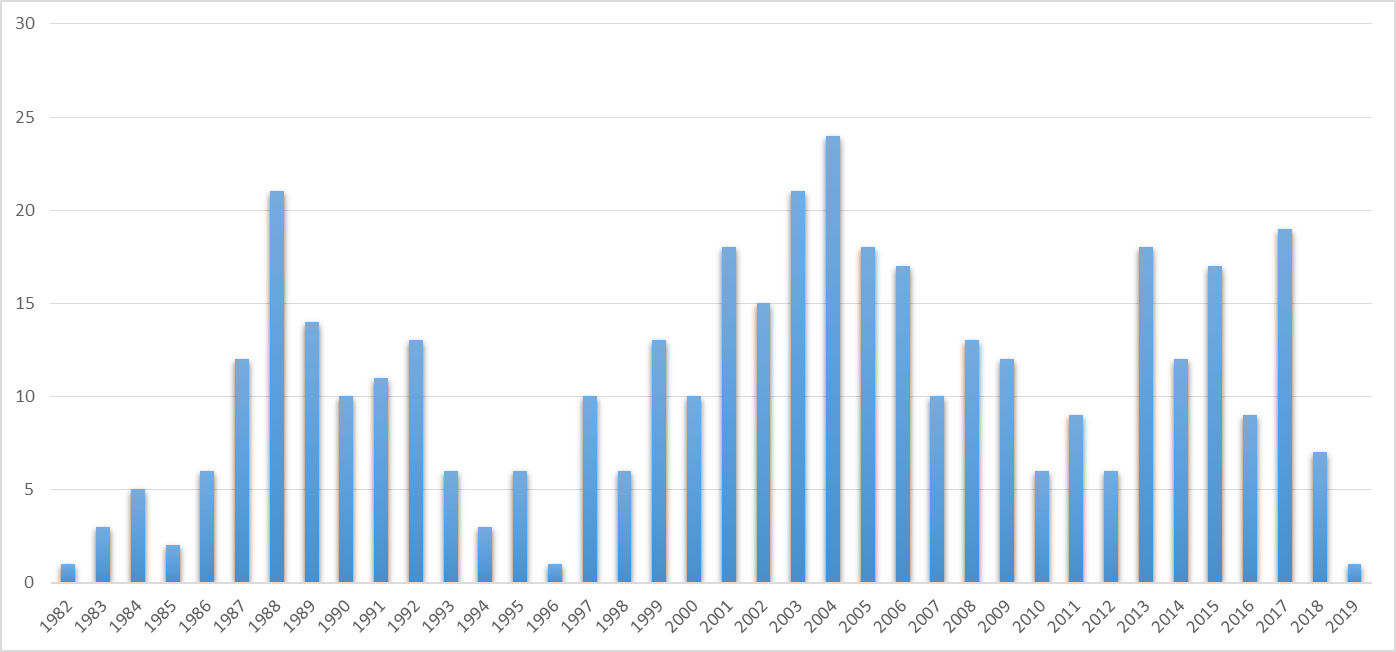

Taking a look at the individual years, there are certain periods that immediately stand out as significant due to the number of performers to emerge based on the date of their first release (Figure 3). The first thing to notice is that the years 2001-2006 have the greatest representation overall. There are a few reasons as to why this might be the case. Firstly, in compiling the list of hip hop performers a good number of those who participated in discussions consumed and discovered UK hip hop around this time meaning they were much more familiar with performers of this era. However, these are also the years when the use of the internet increased meaning more performers had a digital presence as technologies became cheaper and more accessible (Leask, 2009). As a result, for many performers this digital record is still discoverable through internet searches, which proved to be the basis for a lot of this research. The fact that these numbers do not continue into the next decade is possibly due to an apparent growing trend that contemporary performers tend to identify geographically no further than London or UK, meaning they had to be excluded for the purposes of this research. This may well be due to the desire to appeal to a more global audience as British hip hop performers gain more significance around the world. It is more likely that someone from the USA or China has heard of London or the UK than Hackney or Peckham, so going into any more detail is not needed. Another significant time period appears to be the late 1980s. This is likely due to the rise of the britcore style of hip hop that was popular around that time and sparked a scramble by record labels to sign British hip hop acts to capitalise on this (Webb, 2007). The subsequent drop in the middle of the 1990s is indicative of the collapse in this popularity and waning label interest as many performers and fans moved away from UK hip hop in those years (Batey, 2008).

The fact that some years and decades have a larger number of performers emerge than others and that, in some cases, one or two locations are the focus of this suggests there are more localised factors influencing hip hop in the city of London. Smaller, local hip hop scenes are known to exist in London and can sometimes bring with them a more geographically marked sound, for example grime, but is it possible to map these using spatial analysis techniques? The next part of this research will look at whether using cluster and heatmap analysis can help identify potential local hip hop scenes in London where a disproportionate number of performers emerged from the same place during the same decade.

Spatial Analysis

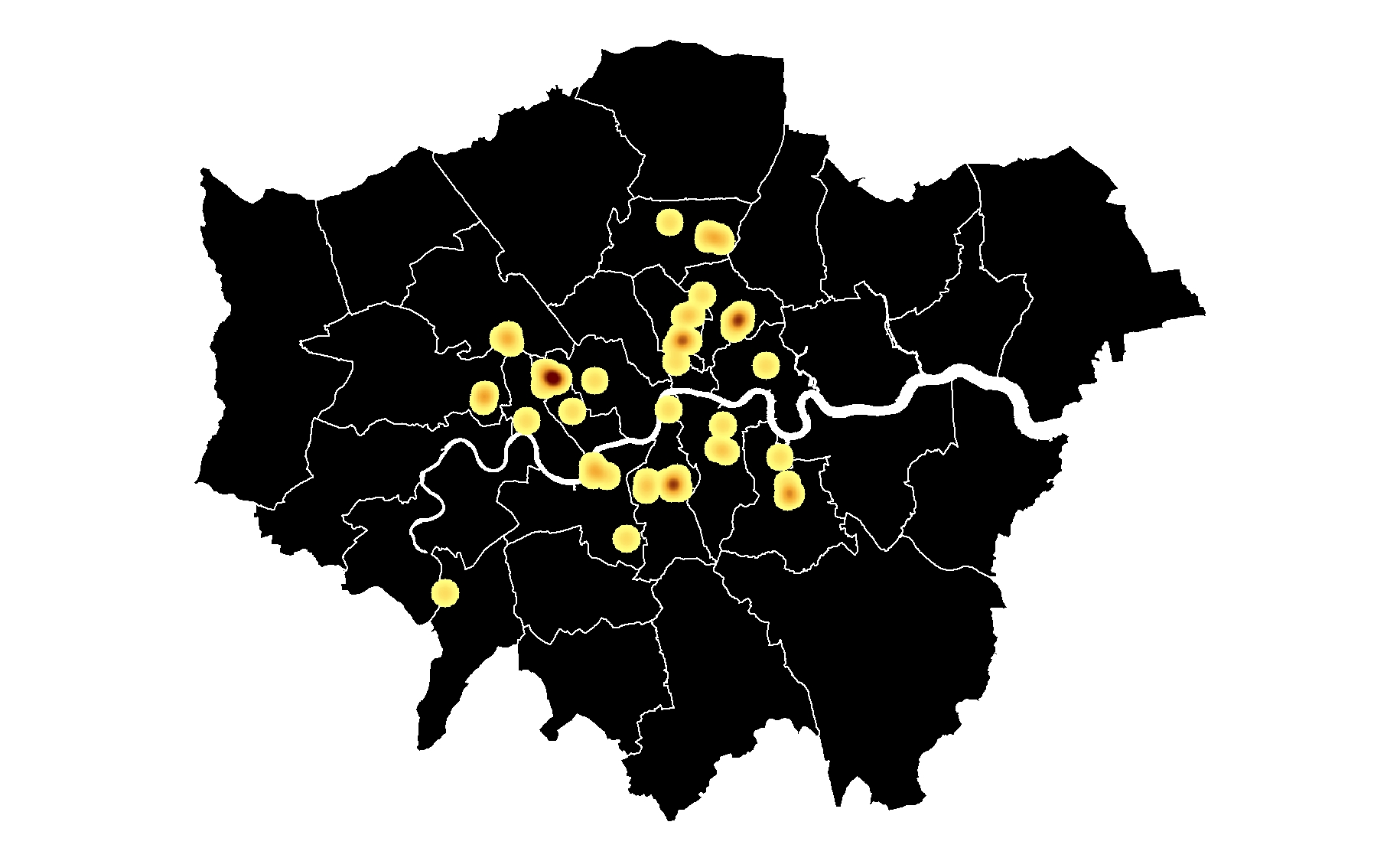

As has been shown so far, there are some locations in London where a greater number of performers emerged during the same decade (Figure 2). However, when looking at this point information on a map, it is not necessarily particularly clear that these patterns exist, as points can overlap or sit on top of each other distorting what is being displayed (Figure 1). Heatmaps are graphical visualisations of clusters of data displayed as colours, generally indicating that the darker the colour the greater the density of whatever is being shown. The decision was taken to use heatmaps as the means to visualise the results of this analysis because they were the most effective in showing clusters of hip hop performers in London. The heatmaps were generated using GIS software, in this case QGIS, after dividing the point data by decade based on the year of a performer's first release (QGIS, 2019).

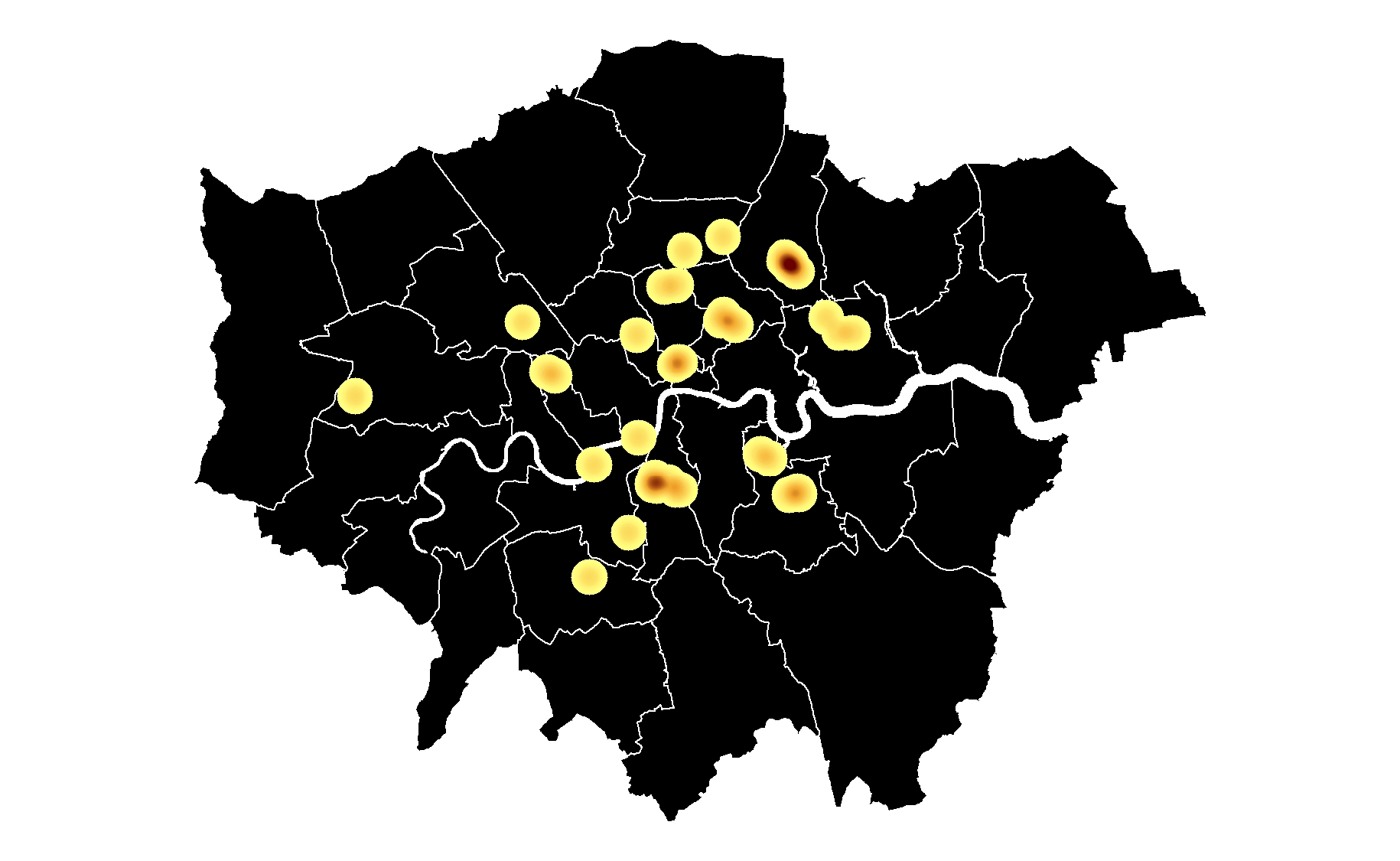

Looking at the results of the 1980's, it is clear that Ladbroke Grove, Hackney, Brixton and Islington are the locations with the most numbers (Figure 4). In particular, Ladbroke Grove stands out with no less that ten performers coming from there during this decade. When looking closer at these, it emerges that quite a few of the early proponents of UK hip hop in London such as Newtrament, Dizzi Heights and MC Sir Drew emerged out of this area, which suggests it was a significant location in the middle of the decade. This may have something to do with Ladbroke Grove having a well-established Jamaican sound system network since the 1950s, something which has also existed in the other highlighted locations (Bradley, 2000). It would have been on these that many performers would have honed their talents, learning the skills of performance and crowd control. The sound systems would also have provided a lot of the support networks for artists in the early days of hip hop in the city that could also point to why more rappers emerged in these places instead of others (Wood, 2009). Similarly, Hackney, Brixton and Islington are also notable for their sound systems in the 1970s and 1980s that may have had an influence on the number of hip hop performers coming out of these locations. Another potential reason why these locations were prominent, is that during this decade many of the key hip hop venues in London were located in the centre of the city, such as the Africa Centre in Covent Garden and Spats on Oxford Street. As a result, being in relative close proximity to these venues, at least in transport terms, may have contributed to the rise of hip hop performers there as opposed to elsewhere, providing a space to perform as well as to meet fellow hip hop heads (McNally, 2009).

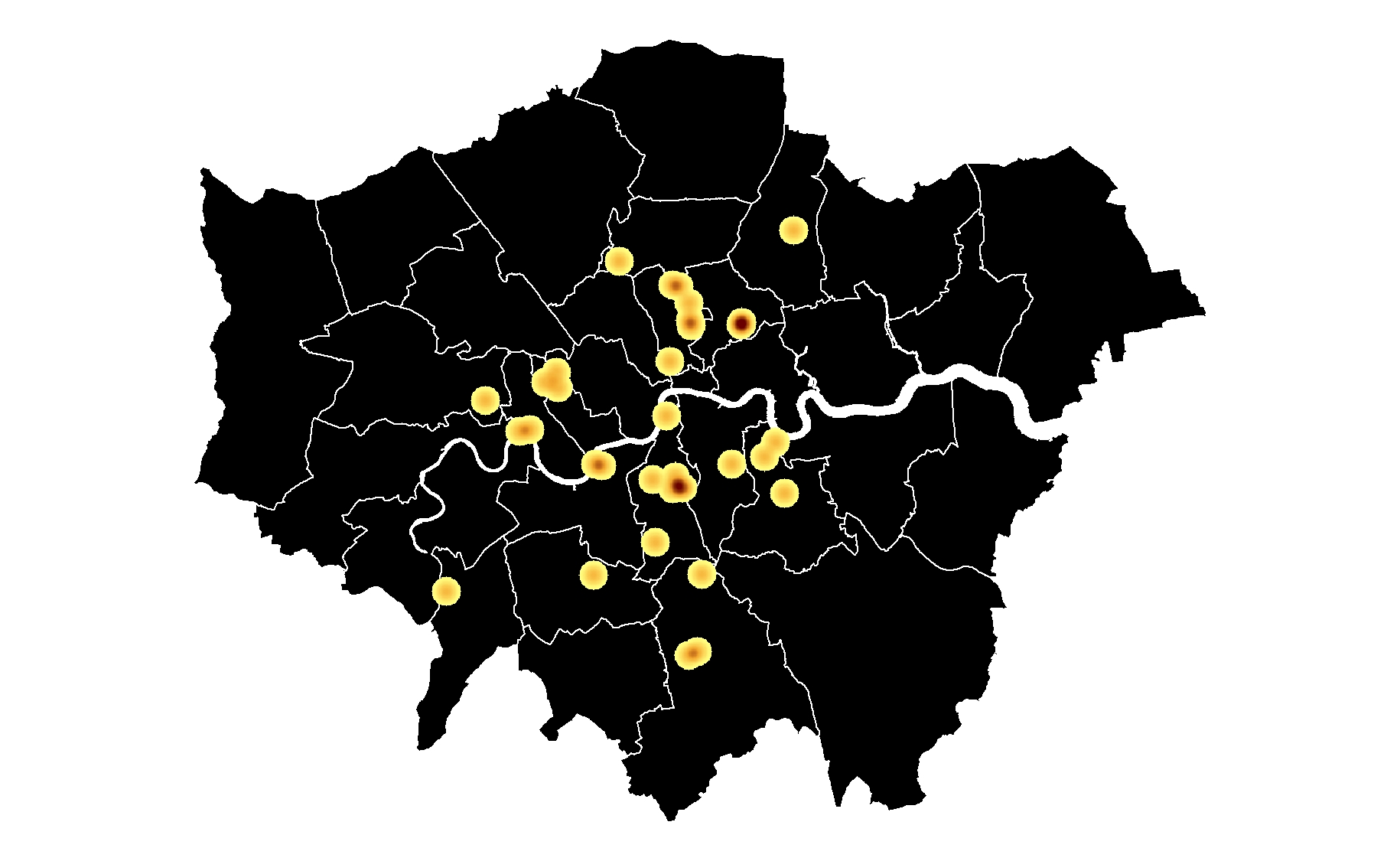

When changing attention to the 1990s, there is evidence of something of a migration from the west to the north east of London (Figure 5). As a result, there is a much higher concentration of performers in the north and north east of the city during this period, with Leyton and Hackney particularly prominent, while the south of London is also still well represented, with Brixton and Stockwell showing significant clusters as well. The 1990s was a significant time for hip hop in the UK with peaks in popularity at either end of the decade but a big decline during the mid-1990s when many performers abandoned the scene for other styles or simply stopped performing (Batey, 2008). As a result, it is almost worth looking at the 1990s as two separate periods; the height of britcore rap in the early half of the decade (Figure 6) and then the recovery period during the latter half (Figure 7). When looked at separately, there is a distinct difference in the distribution of rappers during the two time periods. This very much leaves Leyton as the focus for the first half of the decade, which can be attributed to a large number of britcore artists in the area, which is interesting in itself given that the group credited with starting the style, Hijack, came from Brixton. This suggests that by the early-1990s styles were spreading across the city, possibly due to increased radio play during this time (Wood, 2009). Britcore was a uniquely fierce, fast-paced style of hip hop influenced by the sound of Public Enemy that reached a level of popularity not previously seen for British hip hop. By the mid-1990s, however, much of the support networks had gone with radio stations and record labels abandoning UK hip hop and this is possibly the reason why the distribution has contracted with more marked instances of clustering and a much less sparse dispersal of performers. In the second half of the decade, Hackney and Brixton become the focus but there does not appear to be a specific style associated with these performers. However, as shown in a previous graph (Figure 2), Hackney has an almost continuous presence as a place where hip hop performers emerge suggesting there is a strong foundation of a local scene there even if there isn’t a specific style you can associate it with. Similarly with Brixton, whose performers are also spread across the decade, the area has proven to be a fertile ground for producing artists indicating a strong local scene and support networks for performers. Some of this may be due to those who had been before and the informal networks that had been established that meant that some of the support infrastructure was still present even if popularity had waned (Back, 1996). Another reason why these locations may have been significant in the second half of the decade is due to the rise in open mic sessions and DIY hip hop venues that emerged in these areas in the late 1990s helping to develop a new generation of talent if only in a smaller locale (Kwaku, 1999).

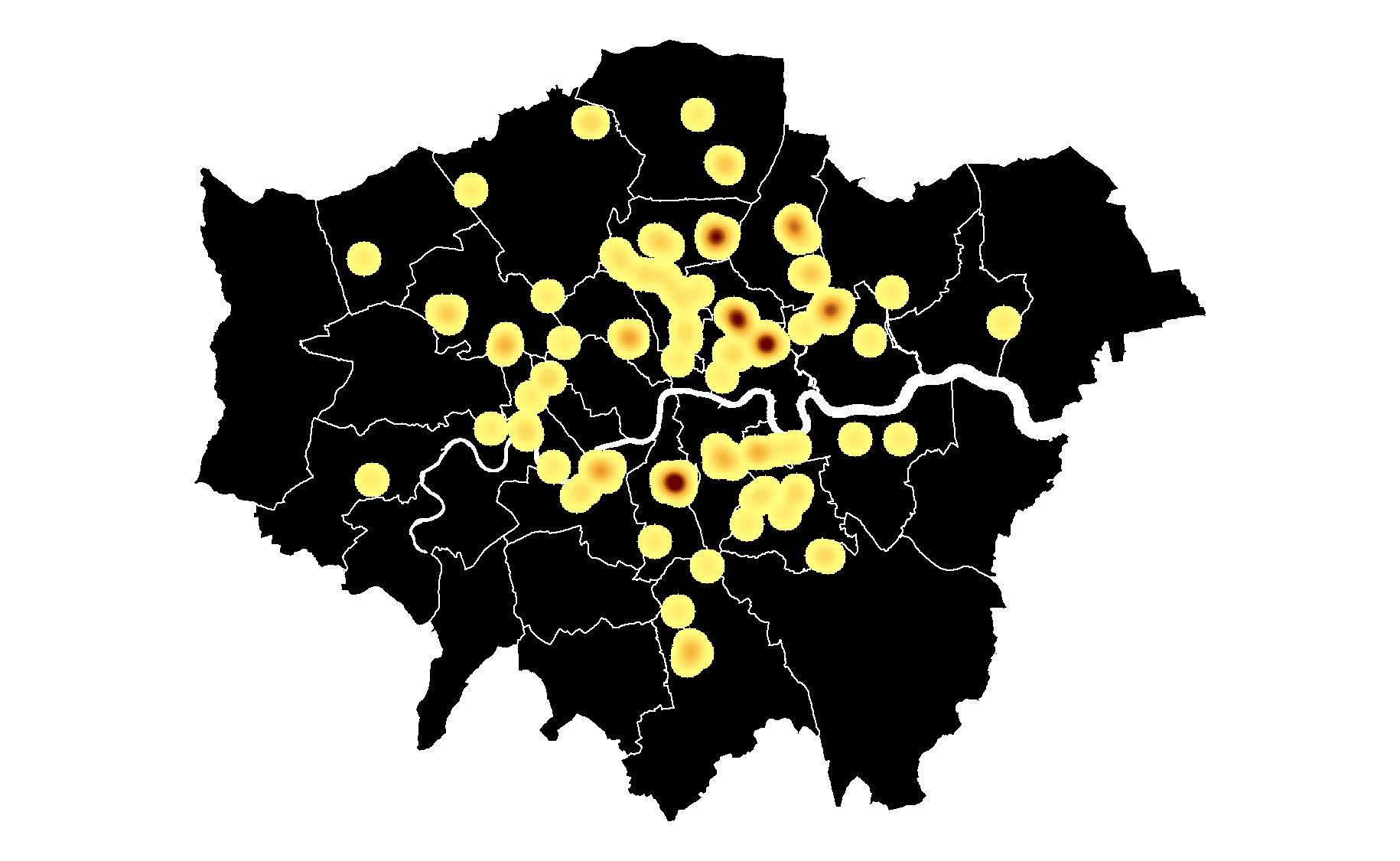

Given that this is one of the most commercially successful periods for UK hip hop with the rise of grime at the beginning of the decade and the globally successful hip-pop style at the end, the fact that so many rappers appeared at this point is understandable. However, there are still the same number of instances of clustering present despite the greater number of performers represented. A lot of this wide spatial distribution of hip hop performers across the city can be attributed to the increased rise and accessibility of the internet and musical technologies that occurred at around the same time. This meant that is was much easier to create, distribute and publicise music, leading to an increase in the number of rappers emerging, particularly those active in releasing music (Blake, 2007). This has also meant that it is much easier for fans and other rappers to find out what else is going on around the city musically, hence explaining why those performing a style associated with a specific geographical area can be found on the other side of the city by the end of the decade. This decade is very much associated with the appearance of a few geographically centred styles of hip hop, the most common of which is grime. Grime was very much focused on the east end of London, particularly Bow, and this is clearly visible on the heatmap where there is an evident group of clusters centred around the likes of Bow and Hackney as well as Tottenham, Forest Gate and Walthamstow. The early years of grime at the beginning of the decade are also marked by a sound whose spread often reached as far as the pirate radio station signal carrying it, many of which could only be heard up to the borough boundary. This was a scene fed and supported almost entirely by pirate radio and makeshift basement studios, with products sold by hand or in local barbershops performed in a vocabulary that, for many outsiders, was impenetrable. Geography and location were very much at the heart of grime and this heatmap visualisation starts to show this based on the number of clusters in such a small area of London (Wheatley, 2010). Another location, however, where there is also a strong cluster is in Brixton to the south, suggesting that grime was not the only geographic focus during the decade. As with the previous decade, however, there does not appear to be a specific style associated with this place. Some could be connected with a sound that appeared between the end of garage and the beginning of grime whose performers included the likes of So Solid Crew, others with grime and some with road rap, that tended to have a focus further south around Peckham. The diverse mixes of hip hop styles being performed in Brixton again solidifies the area’s reputation as a prominent location in the history of UK hip hop throughout its existence.

Taking a look at the most recent decade and the years since 2010, the first thing to notice is that there are barely any clusters present on the map (Figure 9). For the most part, there is an apparent lack of any obvious spatial distribution of hip hop performers across the city with this seeming to be much more ad-hoc and spread out. There are a number of reasons why this is the case, but the two most prominent influences are that of the internet and gentrification. The increasing prevalence of the internet in society, has meant that where you are is a lot less relevant when making music so scenes tend to become digital rather than physical. As a result, the locally-grounded sites of musical interaction, such as the record store and even in some cases the venue, become less significant and the support networks irrelevant as ‘the internet enables a sense of online “imagined community”’ that can include the whole city or even further afield (Kruse, 2009: 210). This is not to say that geography is no longer significant in UK hip hop. However, overt representation to a specific place has become less common, as mentioned earlier with more performers using just London, or even the UK, as their geographic marker as they aim for a more global audience. Nevertheless, there is a clear stand out cluster on the map around Croydon. A lot of these are drill rappers and Croydon has proven to be very much the epicentre of this style. Somewhat surprisingly given the digital era, drill performers often go into even more geographical detail than is the focus of this research. Many of them tend to focus on the specific estate they are from, such as 150 or 67, taking it to an almost hyper-geographical identity representation. Showing that even now geographically centred hip hop scenes can be found in London.

However, there is another impact on hip hop performers in London that is affecting their geographical location and that is gentrification. The rapid rise of gentrification in the last fifteen to twenty years in London has had a huge impact on the lives of a large proportion of people in the city. Gentrification essentially involves a situation where supposedly run down and low income neighbourhoods go through a process of 'regeneration', with the intention of attracting higher income clientele at the expense of the existing residents (Atkinson, 2000). As a result, rents dramatically increase as landlords realise that there are people who would be willing to pay much more to live in that area. This inevitably pushes out the lower income residents who find they cannot afford to live there anymore, and so are forced further out of the city in search of affordable housing. As, traditionally, hip hop performers tend to come from more low income backgrounds, gentrification predictably has an impact over time on the spatial distribution of where performers emerge and this can be seen on the map where the spread is wider than earlier decades. Ironically, in some cases, it can be vibrant local music scenes that draw in these incomers, whose presence ends up having an impact on the performers who attracted them in the first place.

Mapping and Hip Hop

While not the most obvious of mediums to fit together, mapping and spatial analysis techniques can be used to provide additional insights into hip hop that would, perhaps, otherwise be missed. ‘Increasingly, it is argued, geography doesn’t matter’ within music and music scenes, however, hip hop still maintains a strong connection to place that is both explicit and implicit (Kruse, 2009: 210). Hip hop in the UK has been proven to place a particularly strong emphasis on location, especially with the heavily geographical styles that have emerged out of London such as grime, road rap and UK drill. Through this, this research has been able to show that it is possible to perform analysis based on spatial data extracted from hip hop, focusing specifically on performers' origins coming out of London.

As has been shown from the maps produced from this research, over the roughly four decades of hip hop in the city the distribution of performers and centres of music have changed and migrated over time. With the exception of the almost persistent presence of Brixton and Hackney as sites of hip hop performance, the significant locations have moved around the city from the west in the 1980s (Ladbroke Grove) to the north and east in the 1990s and 2000s (Leyton and Bow) and down to the south since 2010 (Croydon). When looked at as a whole, this is an interesting pattern as there does not appear to be an obvious reason why this would be the case. No doubt there are a variety of factors that have resulted in this migration from the physical, such as gentrification (Ladbroke Grove is very different now to the 1980s), to the technical (wider access to music technology and the internet removes the reliance on services like studios and distribution that may be focused in certain locations) to the purely coincidental (right time, right place for those performers). However, more research into this would need to be done to properly see if there is any significance to this pattern. Nevertheless, this is a prime example of how mapping can help visualise something that can trigger and inspire further research.

There are a number of questions to come out of this research that could lead to further discussions and research on the topic. For example, having seen the longevity of places like Hackney and Brixton where there hasn't been an obvious style connected to that place, do local scenes related to a specific style have a shorter lifespan? Do other cities have similar patterns of distribution and migration when it comes to the origins of hip hop performers as London and what could be the causes of this? Is it possible through this cluster analysis approach to predict the location of future local scenes based on the outcomes of one or two years instead of a decade? Any of these could be taken on to further investigate the results that have been presented in this paper. This is not to say that the analysis should stop on the data that has been compiled in this research. There are all kinds of analysis that could be done, analysing demographic statistics could provide some fascinating insights into the relationship between the music, the performers and the sociological and political environment around them. While this has been discussed from an aural and textual perspective, a spatial approach could produce a new angle to the hip hop debate. Another potential focus could be to map hip hop from the perspective of lyric analysis to plot the localities that performers mention in their songs as well as possibly looking to map the origins of words and their migration over time within and without hip hop.

Mapping can be a great way to visualise data and give context to what is being discussed, particularly when it comes to locations, but it does not have to stop there. Depending on the data, further investigation using spatial analysis techniques can help reveal trends or details about music that would otherwise potentially be missed. Everything happens somewhere, including music, but geography, in terms of its spatial side, quite often gets overlooked in discussions about music and musicians. To approach hip hop in terms of place is an often-discussed topic, but there has been little attempt so far in academic circles to involve spatial analysis within this kind of study. While this investigation merely touches the surface of what could be achieved, there is the hope that it can potentially encourage other studies and contribute to the limited research so far completed on UK hip hop.

References

Atkinson, R (2000) “The Hidden Costs of Gentrification: Displacement in Central London”, Journal of Housing and Built Environment, 15 (4), p307-326

Back, L (1996) New Ethnicities and Urban Cultures: Racisms and Multiculture in Young Lives. London UCL Press

Batey, A (2008) “1993 All Rapped Up: On the Home Front”, Hip Hop Connection, issue 227, October, p85

Blake, A (2007) Popular Music: The Age of Multimedia. London: Middlesex University Press

Bondi, L (1993) “Locating Identity Politics” in M. Keith & S. Pile (eds) Place and the Politics of Identity. London: Routledge, p84-101

Bourdieu, P (1993) The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Cambridge: Polity Press

Bradley, A (2009) Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop. New York: Basic Civitas Books

Bradley, L (2000) Bass Culture: When Reggae was King. London: Penguin Books Ltd

_______ (2013) Sounds Like London: 100 Years of Black Music in the Capital. London: Serpent's Tail

Carney, C.P. (2003) “Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s”. Dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College the Department of History, 88, 236, 243. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1175&context=gradschool_dissertations

Celma, O & Nunes, M (2008) “GeoMuzik: A geographic interface for large music collections”, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval

Codrington, R (2005) “The Homegrown: Race, Rap and Class in London” in D. Thomas & K. Clarke (eds) Globalization and Race: Transformations in the Cultural Production of Blackness. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, p299-315

Cohen, S (2012) “Bubbles, Tracks, Borders and Lines: Mapping Music and Urban Landscape”, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 137 (1), p135-170.

Cresswell, T (1996) In Place/Out of Place: Geography, Ideology and Transgression. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Du Noyer, P (2010) In the City: A Celebration of London Music. London: Virgin Books

Emery, A (2009) “Derek B Paved the Way for UK Hip Hop”, The Guardian, 17th November, https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2009/nov/17/derek-b-uk-hip-hop (Accessed 01/09/2019)

Forman, M (2000) “Represent: Race, Space and Place in Rap Music”, Popular Music, 19, p65-90

________ (2002) The ‘Hood Comes First: Race, Space and Place in Rap and Hip Hop. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press

Govaerts, S & Duval, E (2009) “A Web-Based Approach to Determine the Origin of an Artist”, 10th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), p261-266

Hall, S. (1997) “The Work of Representation” in S. Hall (ed.) Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, London: SAGE Publications Ltd., p13-74.

Hancox, D (2018) Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime. London: William Collins

Hesmondhalgh, D & Melville, C (2001) “Urban Breakbeat Culture: Repercussions of Hip Hop in the United Kingdom” in T. Mitchell (ed) Global Noise: Rap and Hip Hop Outside the USA. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, p86-110

Hess, M (2009) Hip Hop in America: A Regional Guide. Santa Barbara: Greenwood

Jeffries, M (2011) Thug Life: Race, Gender and the Meaning of Hip hop. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Knees, P., Schedl, M & Pohle, T (2008) “A Deeper Look into Web-Based Artist Classification of Music Artists”, Proceedings of 2nd Workshop on Learning the Semantics of Audio Signals, Paris, France, p1-14

Krims, A (2007) Music and Urban Geography. London: Routledge

Kruse, H (2009) “Local Independent Music Scenes and the Implications of the Internet” in O. Johansson & T. Bell (eds) Sound, Society and the Geography of Popular Music. Farnham: Ashgate, p11-31

Kwaku (1999) “Brit Rap: Indies Rule Britannia when it Comes to Breaking Rappers”, Billboard, 111 (49), 4th December, p54

Lambiotte, R & Ausloos, M (2006) “On the Genre-fication of Music: A Percolation Approach”, The European Physical Journal B, 50 (1-2), p183-188

Lashua, B (2011) “An Atlas of Musical Memories: Popular Music, Leisure and Urban Change in Liverpool', Leisure/Loisir, 35 (2), p133-52.

Leask, H (2009) “One Radio Big Dog Who's Still on Top: Tim Westwood”, Hip Hop Connection, issue 231, March, p56

Lipsitz, G (1994) Dangerous Crossroads: Popular Music, Postmodernism and the Poetics of Place. London: Verso

Lund, J (2007) “Musicology: Mapping Music and Musicians” in D. Sinton & J. Lund (eds) Understanding Place: GIS and Mapping Across the Curriculum. ESRI, Inc., p259-268

Maguire, D.J. (1991) “An Overview and Definition of GIS”, Geographical information systems: Principles and applications, 1, p9-20

Massey, D (1994) Space, Place and Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press

McNally, J (2009) “Family Quest: They’re Back! 25 Years after Dropping the First Authentic UK Hip Hop Record”, Hip Hop Connection, 230 (January/February), p150-153

Reynolds, S (2009) “Grime” in R. Young (ed) The WIRE Primers: A Guide to Modern Music. London: Verso, p77-85

Schloss, J (2004) Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip Hop. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press

Sinton, D & Huber, W (2007) “Mapping Polka and Its Ethnic Heritage in the United States”. Journal of Geography Vol: 106. P41-47

Speers, L (2017) Hip Hop Authenticity and the London Scene: Living Out Authenticity in Popular Music. London: Routledge

Taylor, S., Arrowsmith, C & Cook, N (2014) ““A Band on Every Corner”: Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes” Geospatial Science Research 3, p1-11

Unwin, D.J. (1996) “GIS, Spatial Analysis and Spatial Statistics”, Progress in Human Geography, 20(4), p540-551

Webb, P (2007) Exploring the Networked Worlds of Popular Music: Milieu Cultures. London: Routledge

Wheatley, S (2010) Don’t Call Me Urban: The Time of Grime. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Northumbria University Press

Wood, A (2009) ““Original London Style”: London Posse and the Birth of British Hip Hop”, Atlantic Studies, 6 (2), p175-190